IASI Snowsports

Tasks and constraints in skill development

Issue #4 By Richard Barbour

As an experienced coach, mentor and educator I have a background at artificial ski centres and the mountain environment. Specialising in coach development and professional qualifications coaching I have run a snowsports school and worked with a wide range of skiers including through to the Paralympic talent pathway. I am Head Coach of Gloucester Adaptive Skiing, coaching skiers and running a development programme for instructors, coaches and their mentors.

The relevance of tasks

In recent years there has been a surge in popularity of a tool for session design and execution called the Constraints Led Approach (CLA) which is strongly linked to tasks.

As someone whose learning has involved a significant emphasis on task-based approaches I have been reflecting and experimenting with CLA in my coaching practice and presented on the topic.. This article takes the principles of CLA and demystifies sometimes obscure language to help you embrace the use of tasks in skill development. Task-based approaches and a related shift in the performers’ attentional focus enrich the learning experience for both performer and instructor.

CLA originated from the theoretical work of Karl Newell in 1986 and has been further developed by academics in the UK and North America including Professor Keith Davids and Dr Rob Gray. There are some references to further resources at the end of the article.

The history of snowsport teaching systems includes many that have a strong technical focus. Think back to instructor training and exams that you have done. How much emphasis was placed on form (how it looks) compared with outcome in relation to intention? I recall a superb display of the Austrian National Teaching System at the IVSI Congress and its strong emphasis on form at various stages of the learner progression. Yet when I went skiing with the same trainers their skiing exhibited radically different movement solutions.

Technique has considerably influenced the snowsport teaching profession and left a legacy. As a coach developer I regularly meet instructors who default to technical analysis and technically biased feedback, mainly influenced by the culture they were exposed to whilst learning. They verbalise their analysis to their skiers who become pre-occupied with how it looks and the value judgements of their instructor. A skewed perception can develop that skill is overwhelmingly judged.

Have you heard this one?

How many ski instructors does it take to change a lightbulb?

Ten.

One to change the bulb and the other nine to criticise their turns. Baboom!

Is skill measured or judged?

When thinking about skill it can be useful to consider the different snowsport disciplines.

The podium is full of people whose skill is measured, judged or both. A straightforward example is slalom racing. The winner is the competitor who gets to the bottom the fastest whilst making a rules-legal descent. The clock tells all. As those who have trained for the speed test will know, the outcome is purely measured.

Mogul competition is very different. 60 percent of the result is based on judgement of the turns; 20 percent on jumps and 20 percent speed – 80 percent of the outcome is based on judgement.

Big Air, park and pipe competitions are purely judged. 100%.

Discipline considerations therefore play a huge part in the participant’s goals and coaching programme. So when teaching or coaching we should be alert of the aspirations of the performer. What do they want to achieve, including:

Where do they want to ski or board?

How important to them is the look?

How they feel about it?

Is the emphasis on outcomes?

Components of the Constraints Led Approach

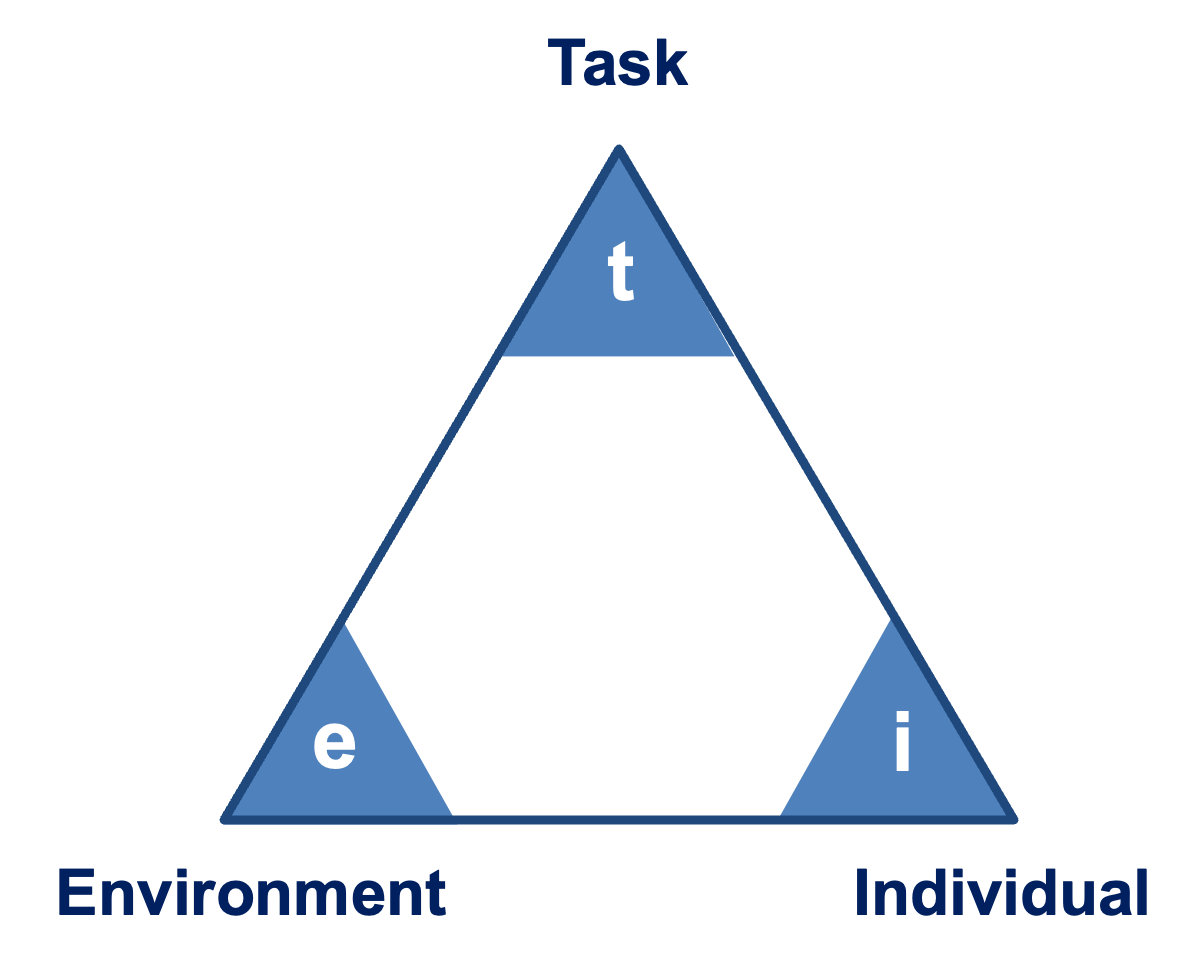

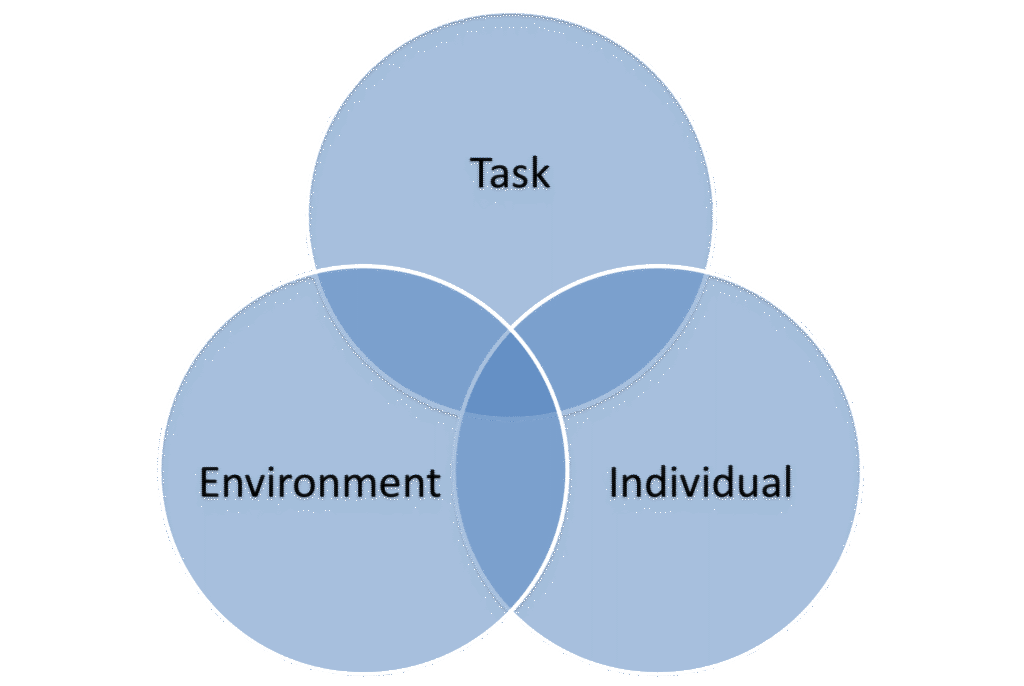

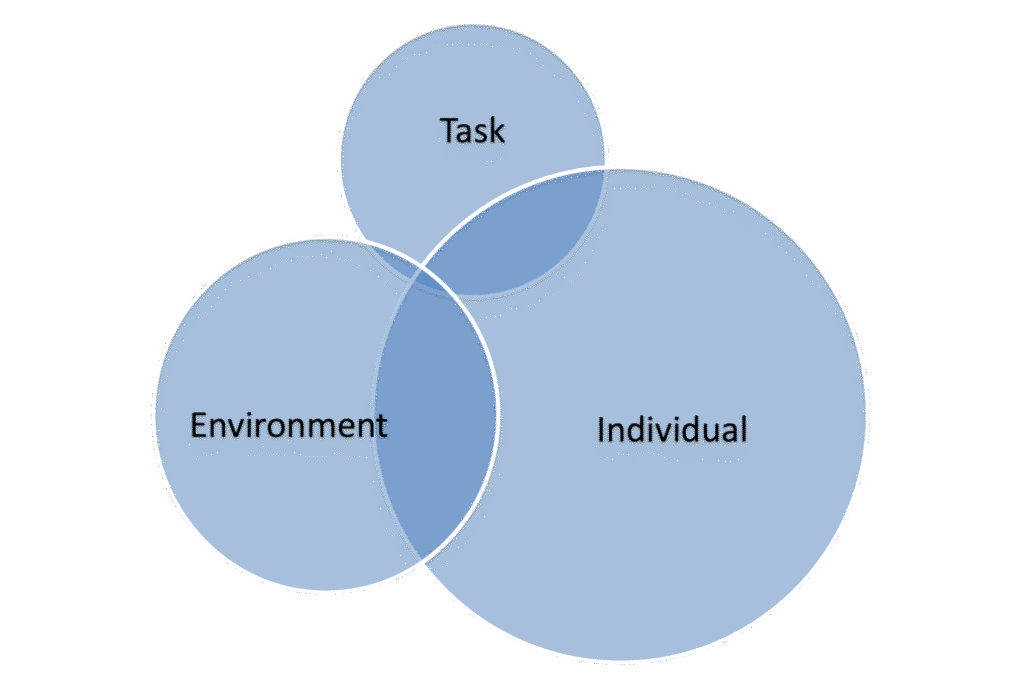

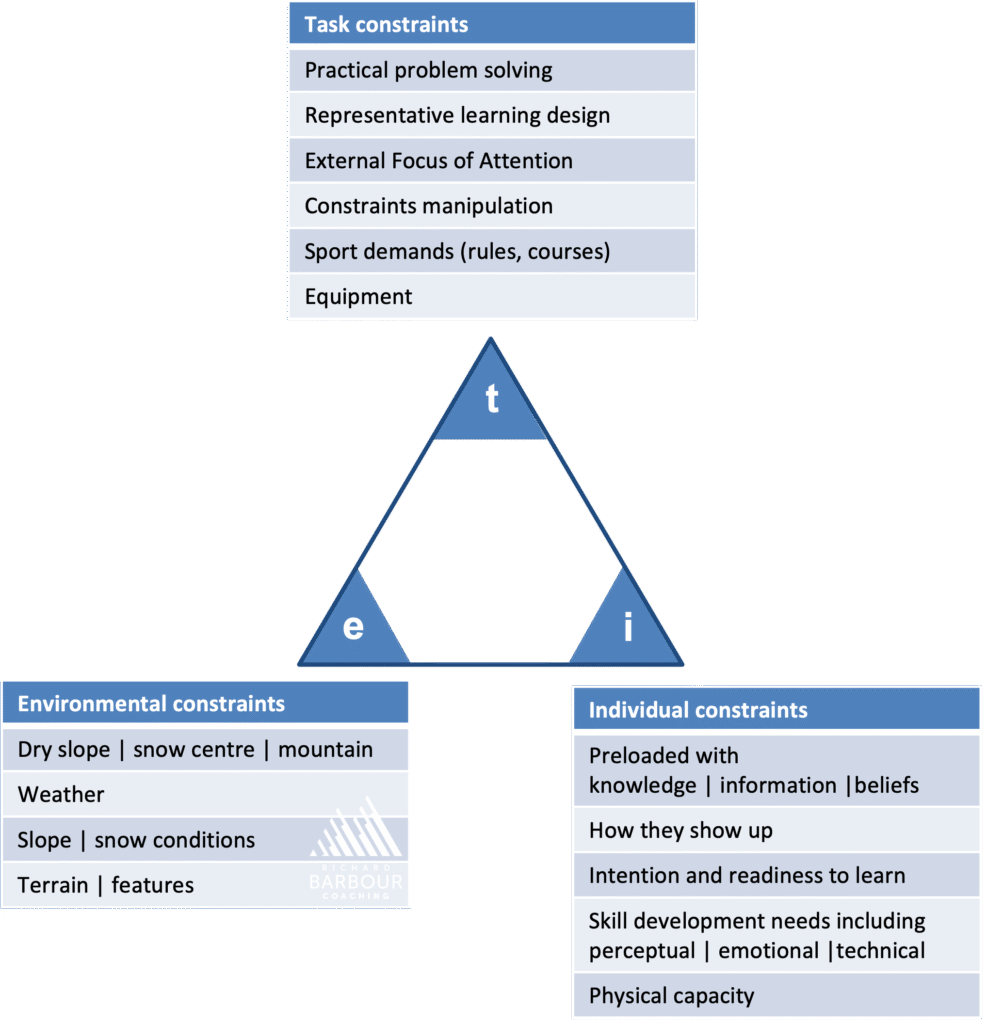

The Constraints Led Approach is based on three inter-related factors or constraints that influence the learning environment: task, environment and individual.

Task constraints

Tasks play a huge part in skill development. They enable the learner to focus externally and provide them with opportunities to make functional movement solutions through a process called self-organisation. This can be hugely powerful because the learner is generating their own sensory feedback whilst making arcs. This considerably amplifies the concurrent information directly available to them and they become less reliant on external judgmental feedback. Tasks and task achievement provide opportunities for a simple, yet powerful, intrinsic feedback loop (a significant topic for another article).

Task constraints mainly relate to a practical problem for the learner to undertake. For example:

making arcs three mats wide on a dry ski slope

performing rhythmically linked arcs in time with a metronome

choosing a specific line in moguls, such as the crests

navigating a stubbie course.

Task constraints can also include factors that impact on the completion of the task such as equipment and competition rules. For example skiing on shorter skis to enable carving at slower speeds or skiing with different skis on each foot to heighten awareness of equipment behaviour.

Developing functional movement solutions through self-organisation is in stark contrast to trying to perform using pre-determined techniques. Limited or no technical instruction may be needed for the learners to achieve the task and performance can be shaped by placing constraints on the task. Examples of constraints include:

aiming tasks

line in relation to stubbies

gaining grip at a certain part of the arc

spraying snow deliberately in certain parts of the arc

The instructor needs the technical knowledge to shape the tasks but it is not necessary to make technique the performers’ focus.

Environment constraints

These include the conditions on the hill, whether they be artificial ski slope surfaces or the mountain environment. It can include weather and the setting or nature of participation, be it for recreation or competition. For example, a plastic ski slope is often defined as a closed environment because the terrain is relatively fixed and conditions are relatively similar from day to day. On a mountainside there is a plethora of environments to explore including terrain and snow conditions. When developing skill it can be useful to manipulate the tasks by doing them on slopes that the performers can easily descend, therefore removing emotional barriers to their development. The learning can be gradually stress-tested on more challenging terrain or snow conditions as part of variable practice (something that CLA practitioners refer-to as “repetition without repetition”).

Some examples of exploiting environmental constraints include:

Using shallower terrain to develop carving activities so that the learner perceives low threat when skiing faster

Finding patches of snow in between glazed areas as part of a tactical approach to descending glazed pistes

Using small bumps to develop choice of line before trying bigger moguls

Individual constraints

The individual is the performer in front of you and how they show up both physically and mentally. They arrive pre-loaded with attributes some of which cannot be directly influenced by the instructor but must be taken account of, such as their fitness level.

This pre-loading also includes (pre)perceptions including knowledge, information and beliefs about how to ski. This can sometimes include strong influences from previous tuition or coaching and can be a significant barrier to self-organised learning. I have experienced learners who are so wedded to strong technical models learnt with others that they have rejected alternative approaches. Other constraints may include life-factors such as work, family, illness or childcare that have psychological impact on their capacity to engage with specific activities either in the moment or training in general.

The word constraint can conjure perceptions of obstacles to or limitations on performance whereas, in reality, they are factors or design elements that can be manipulated to invite action and promote skill development. Note the use of the word invite as the skier must be invested, willing, reasonably able and activated to engage with the task. They must openly contract with you to participate in this way which can be a significant challenge to those who have been conditioned to expect technique-based feedback.

It can be useful to view these elements as a Venn diagram. In its simplest form it can look like this:

A useful adaption is to consider that the bubbles have a total volume that is shared between them. This can help with prioritising the relevant constraint factors in the situation or moment. For instance, the learner may be fearful and their psychological, emotional, needs may need prioritising over other aspects of what the instructor had planned:

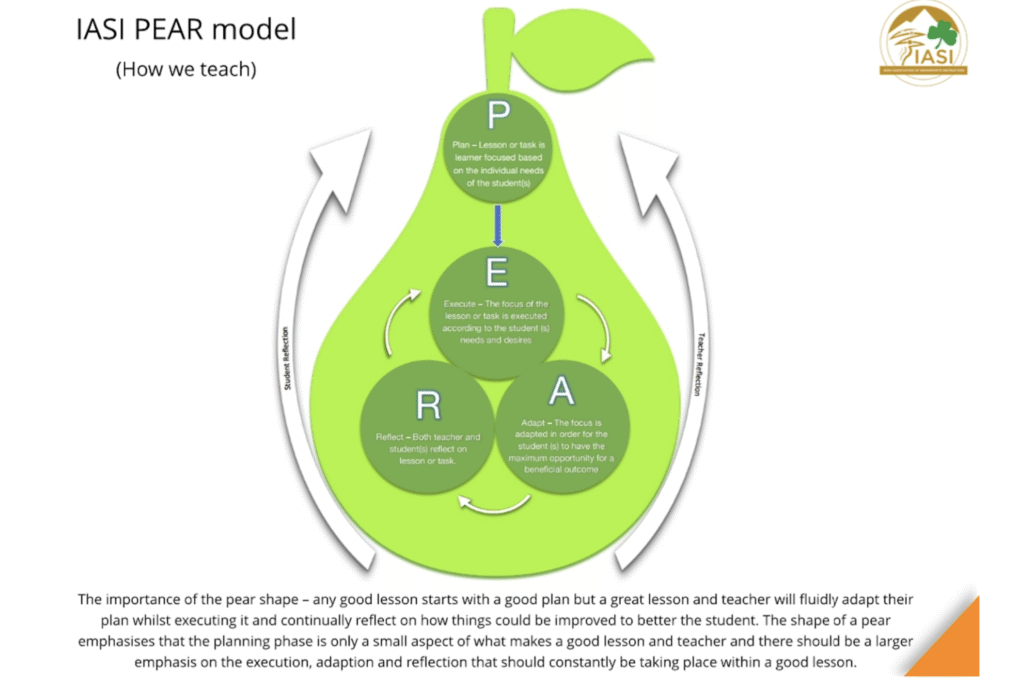

This adapted model supports a reflective approach to teaching and can help the instructor or coach with their practice design and evaluating the emphases chosen for the session and how effectively it is progressing. It empowers dynamic manipulation of the sessions to maximise benefits to the learner. This links well with the IASI PEAR Model of Plan, Execute, Adapt and Reflect.

An important part of task setting is that the outcomes are representative of what the learner will ultimately do when performing skilfully in an open environment. I have met many skiers who arrive pre-loaded with beliefs relating to technique, for instance that they should “look down the valley” in every turn shape imaginable. This belief significantly hinders their adaptability and capacity for all-mountain skiing. Another example is of skiers taught to deliberately and forcefully close their skis together whilst skiing too slowly during the plough parallel learning phase. This makes the ski pivot around the tip and uses different muscles groups to those used when effectively skiing parallel: it is preferable for the activities to encourage appropriate speed and turn shape so that the inner ski unwinds naturally by rotating under the foot.

Summary

Recent and ongoing research into motor learning has investigated and developed CLA from Newell’s initial work. The three components (aka constraints) of task, environment and individual have strong impact on the design and execution of training sessions and lessons. The emphasis placed on each of these constraints is situation-specific, variable and strongly influenced by the pre-loading of the individuals; what they bring to the session. Here is a summary of the model in relation to snowsports:

One of the tricks of this approach is to make the learning design representative of the sport. When choosing to use drills during a session ask yourself whether they add value to the intended outcome or if they are hindering it. How does your drill of storks, javelins, supermans or face-down-the-valley relate to or represent aspects of the complete performance? When teaching or coaching on the dry slope or confines of a dome, consider where the activities fit into the learners’ aspirations for performance on the mountain and reflect on whether the activities and learning are transferable to that environment.

Next time you are teaching, consider if you can use your technical know-how to establish tasks that create useful behaviours and sensory feedback for the learner. Can the learner develop their skill without the need for value judgements based on how it looks?

Tasks help the learners to solve practical problems and come up with functional movement solutions rather that fixed techniques. They become more adaptable and responsive in the moment. Our role as instructors and coaches then becomes an architect of the learning environment and facilitator of learning.

IASI’s recent Future Strategy Report highlighted a central value of the education system being rooted in outcome and skill-based approaches to learning. So be ahead of the curve and use this article to inspire some task setting in your next session!

Watch this YouTube short to see task architecture in action.

About the author

Richard is a coach and civil engineer by training and has over 30 years’ experience and numerous qualifications in coaching within sport and business. He works as a snowsport consultant, snowsport coach, coach developer, personal coach and podcaster. He is Head Coach of Gloucester Adaptive Skiing, a club providing access and pathways in snowsports for people with disabilities. He was manager and head of snowsports at Gloucester Ski & Snowboard Centre. His award-nominated podcasts have a global audience from the west coast of America to New Zealand.

If you would like to get in touch to discuss any aspects of this article you can find him at www.richardbarbourcoaching.co.uk, www.linkedin.com/in/richardsbarbour or his YouTube channel

© Richard Barbour 2025

Resources

Here are some useful resources to explore the topic further (click on the images to access the links):

Want to write for Inside Edge?

All IASI members are welcome to contribute to Inside Edge. If you’d like to have your article published by IASI, please email Blue with your ideas and she’ll take it from there.

Latest Posts

- Tasks and constraints in skill development

- Race training and the instructor journey

- The Off-Season Advantage

- Free the Heel!

- Rich Egan – A Day in the Life

- Introducing Michael Edwards – Head of Education

- IASI delivering Freestyle Coach Level 1

- A Day in the Life – Ali Smith

- IASI and Interski Information

- Important Note from the ISIA Board